Verilator Visual Simulator: Technical Architecture

Overview

When I was working on the FPGAScope project, I created this Verilator-based visual simulation tool to connect RTL hardware description with real-time interactive visualization. The system demonstrates how modern HDL simulation can integrate with SDL2 graphics to create responsive, dual-display visual testbenches for complex digital designs. These include PS/2 keyboard interfaces, VGA display controllers, and inter-FPGA communication protocols. The architecture highlights the power of cycle-accurate simulation combined with immediate visual feedback, speeding up the hardware development cycle from weeks to hours.

I built this tool because traditional FPGA development requires long synthesis, place-and-route, and programming cycles - often taking 15-30 minutes per iteration - before you can see how your design behaves on real hardware. This simulator eliminates that bottleneck by running Verilog/SystemVerilog designs in a high-performance C++ environment at millions of cycles per second, with visual output rendered at 60fps. This enables rapid prototyping, real-time debugging, and immediate design iteration that would be impossible with regular FPGA toolchains.

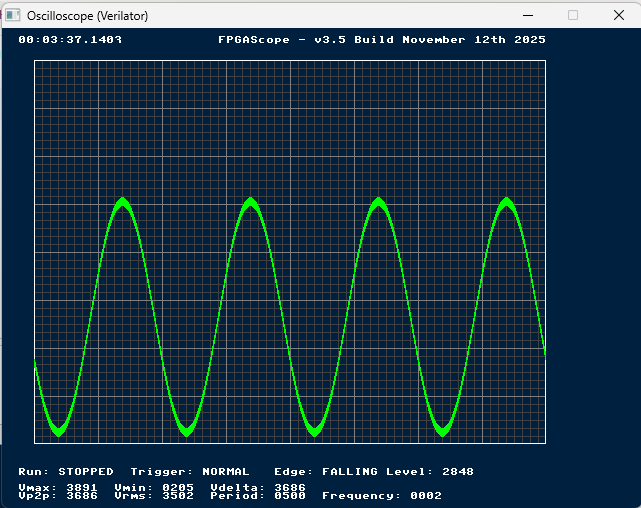

Early Development: FPGAScope Prototyping

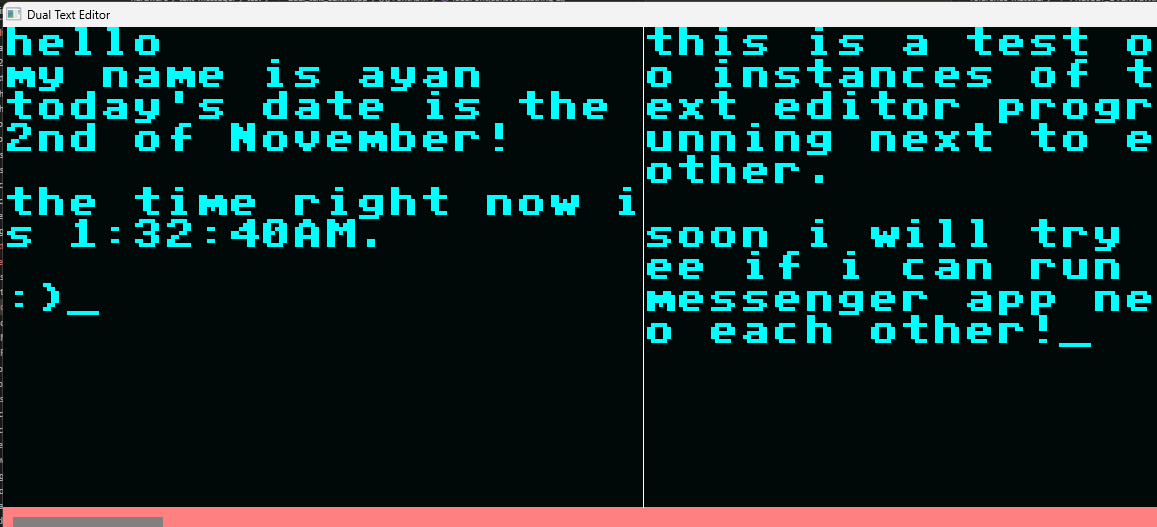

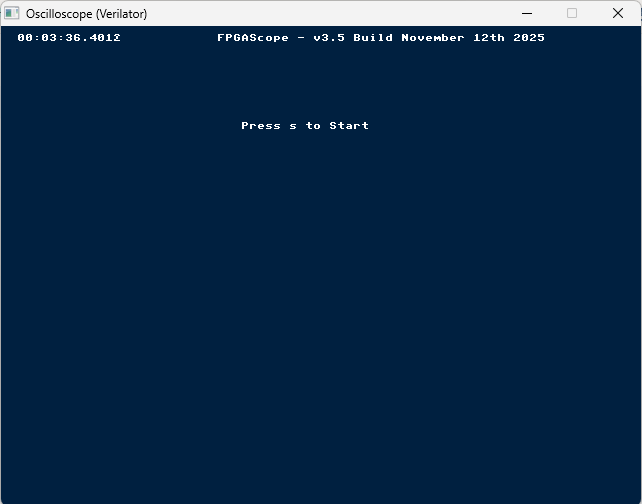

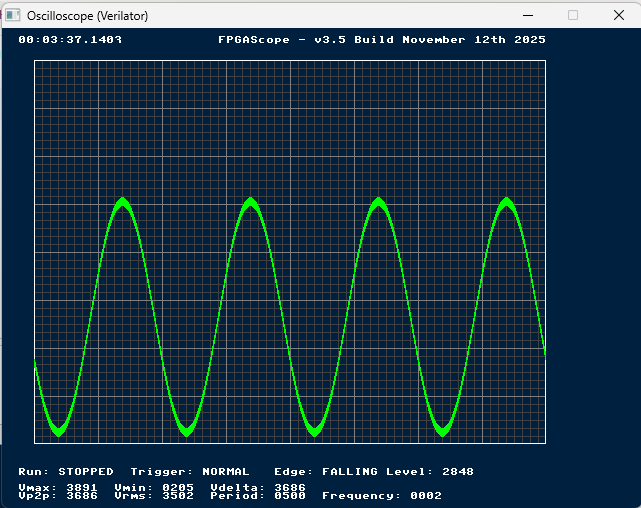

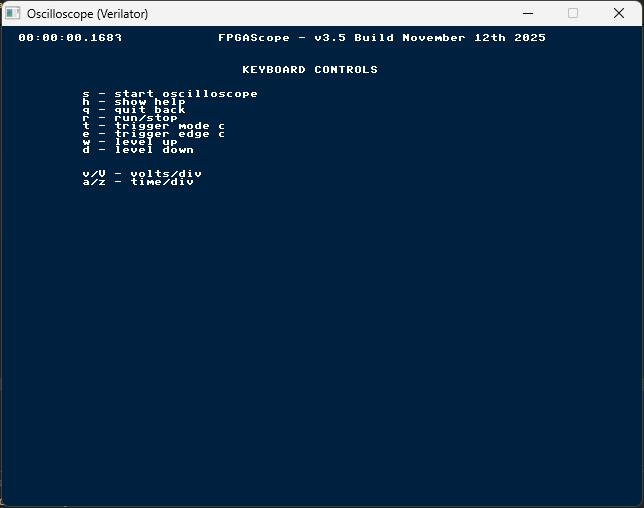

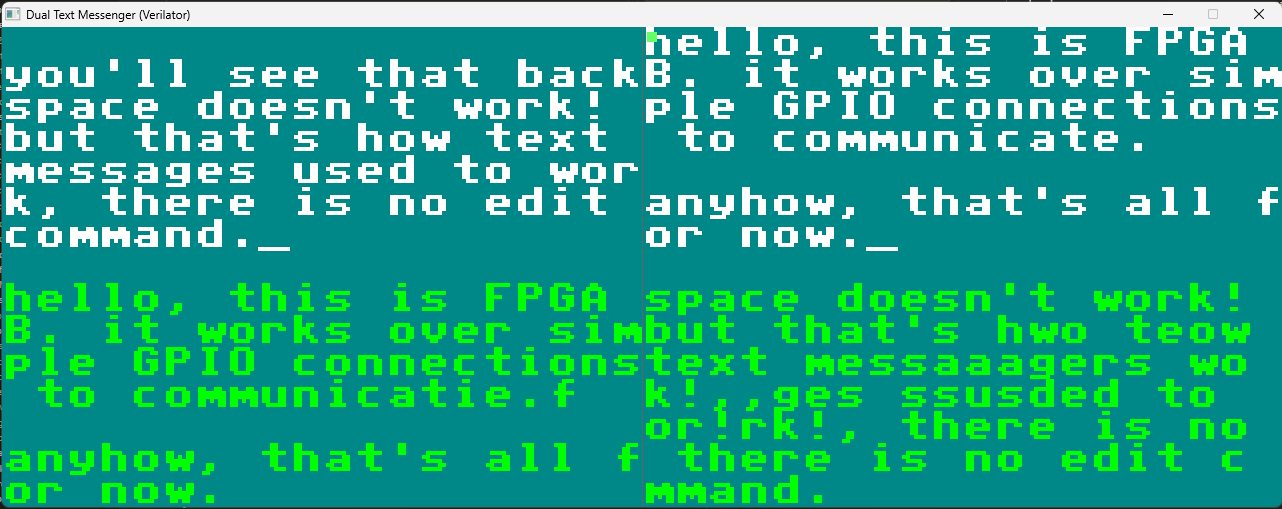

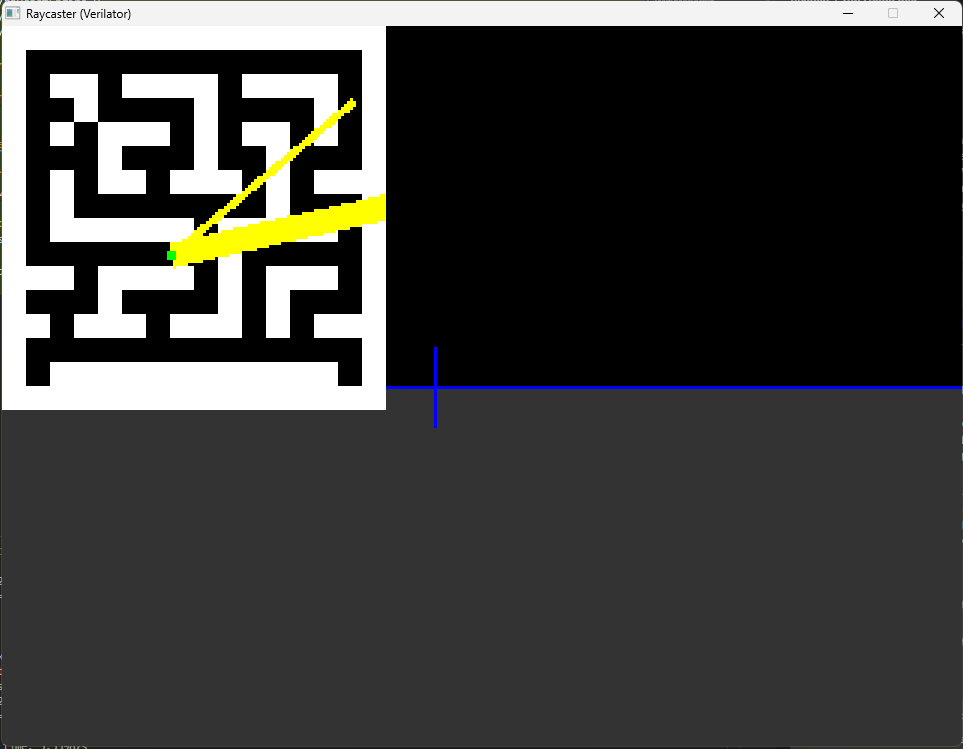

These images above demonstrate the initial development phase of my FPGAScope project, showing how quickly functional visualization can be achieved when the entire development loop occurs in software simulation rather than hardware. The left image shows an early-stage text-based debug interface with VGA signal generation, while the right image presents a more refined dual-pane visualization displaying both raw signal timing and rendered output. What makes this amazing is the iteration speed - modifications to the VGA controller, font rendering logic, or text buffer management can be tested within seconds rather than the typical 20-minute FPGA compilation cycle. This acceleration factor of approximately 100x transforms the development experience from laborious trial-and-error into fluid, exploratory design.

This third FPGAScope image reveals a mature visualization system with clean text rendering and proper VGA timing synchronization. I could reach this level of polish so rapidly because of the simulator's architecture. Every clock cycle's VGA outputs (horizontal sync, vertical sync, RGB color values, and visible region flags) are captured and immediately rasterized to an SDL2 texture. Modifications to character ROM lookup tables, cursor positioning logic, or display refresh rates are instantly visible, creating a tight feedback loop that encourages experimentation and refinement. This development speed is simply unattainable when constrained by physical hardware programming cycles.

Architectural Overview

The Verilator Simulation Engine

I chose Verilator because it's an open-source SystemVerilog and Verilog compiler that transforms HDL designs into highly optimized cycle-accurate C++ models. Unlike traditional event-driven simulators (ModelSim, Questa, VCS) that interpret RTL constructs at runtime, Verilator performs ahead-of-time compilation, generating native machine code that executes 10-100x faster than interpreted simulation. The compiled model exposes all module ports as C++ class members, enabling seamless integration with testbench code written in C++. This makes Verilator ideal for performance-critical applications like continuous integration testing, hardware-software co-verification, and as given above real-time visual simulation.

Verilator follows the following workflow:

- Parses the input Verilog source files and constructs an abstract syntax tree (AST) representing the design hierarchy, always blocks, continuous assignments, and instantiated modules.

- Performs extensive optimization passes including constant propagation, dead code elimination, and combinational loop detection.

- Splits the design into separate functions for combinational logic evaluation (

eval()) and sequential state updates (eval_settle()), ensuring correct separation of blocking and non-blocking assignments. - Emits C++ source files organized into a class hierarchy where the top-level module becomes a C++ object with public member variables for each port signal.

The generated code structure typically produces several key files in the obj_dir/ output

directory. The main header (Vtop_module.h) declares the top-level simulation class with port

members, clock inputs, and control methods. Implementation files (Vtop_module.cpp,

Vtop_module__Slow.cpp) contain the synthesized logic split into fast-path and slow-path

functions. Internal module state is stored in Vtop_module___024root.h, using mangled names to

avoid C++ keyword collisions. Symbol tables (Vtop_module__Syms.h) provide debug access to

internal signals. The build system generates a makefile (Vtop_module.mk) that compiles all

components and links them with the Verilator runtime library (verilated.cpp,

verilated_threads.cpp).

// Example of typical Verilator API usage

#include "VtbDualMessengerVerilator.h"

#include "verilated.h"

VerilatedContext* contextp = new VerilatedContext;

VtbDualMessengerVerilator* top = new VtbDualMessengerVerilator{contextp};

// Initialize inputs

top->clock50MHz = 0;

top->resetn = 0;

top->scan_code_A = 0;

top->key_action_A = 0;

// Run simulation for one clock cycle

top->eval(); // Evaluate combinational logic

top->clock50MHz = 1;

top->eval(); // Rising edge trigger

top->clock50MHz = 0;

top->eval(); // Falling edge and settle

// Read outputs

uint8_t red_value = top->red_A;

bool vga_visible = top->visible_A;System Architecture: Testbench, Hardware, and Visualization Layers

The simulation system is architected in three distinct layers, each with clearly defined responsibilities and interfaces. At the foundation lies the Hardware Layer, containing the actual Verilog RTL modules being simulated. This includes the text editor/messenger application logic, VGA driver modules that generate sync signals and pixel data, PS/2 driver modules that decode keyboard scan codes, and peripheral memory components like font ROMs and scancode lookup tables. These modules are written in synthesizable Verilog and are identical to what would be deployed on physical FPGA hardware, ensuring that simulation results accurately predict real-world behavior.

The middle Testbench Layer provides stimulus generation and signal routing between C++ and

Verilog domains. This layer is implemented as a special top-level Verilog module (e.g.,

tbDualMessengerVerilator) that instantiates the hardware modules and exposes critical control

and observation ports to Verilator. The testbench handles several key responsibilities: it declares input

ports (clock50MHz, resetn, scan_code_A/B,

key_action_A/B) that accept stimulus from C++ code; it instantiates PS/2 keyboard simulator

modules (ps2KeyboardVerilator) that convert byte-level scan codes into realistic serial PS/2

clock and data waveforms; it connects communication signals between multiple board instances, emulating

inter-FPGA GPIO or serial links; and it exposes output observation ports (red_A,

green_A, blue_A, hSync_A, vSync_A,

visible_A, xOrd_A, yOrd_A) that allow C++ code to capture VGA signals

in real-time.

module tbDualMessengerVerilator(

input clock50MHz,

input resetn,

input key_action_A,

input [7:0] scan_code_A,

input key_action_B,

input [7:0] scan_code_B,

// VGA outputs from board A

output hSync_A, vSync_A,

output [9:0] xOrd_A, yOrd_A,

output visible_A,

output [3:0] red_A, green_A, blue_A,

// VGA outputs from board B

output hSync_B, vSync_B,

output [9:0] xOrd_B, yOrd_B,

output visible_B,

output [3:0] red_B, green_B, blue_B

);

wire [7:0] commOut_A, commOut_B;

wire commValid_A, commValid_B;

// Cross-connect communication channels

wire [7:0] commIn_A = commOut_B;

wire commValidIn_A = commValid_B;

wire [7:0] commIn_B = commOut_A;

wire commValidIn_B = commValid_A;

// Instantiate board A

textMessenger boardA (

.clock50MHz(clock50MHz),

.resetn(resetn),

.ps2Clk(ps2Clk_A),

.ps2Dat(ps2Dat_A),

.hSync(hSync_A),

.vSync(vSync_A),

/* ... VGA and comm ports ... */

);

// Instantiate board B

textMessenger boardB (

/* ... similar port connections ... */

);

endmoduleThe top Visualization Layer is implemented entirely in C++ and handles window management, user input, pixel capture, and frame rendering. This layer uses the SDL2 (Simple DirectMedia Layer) library to create cross-platform graphics windows with hardware-accelerated texture streaming. The core responsibilities include: SDL2 window and renderer initialization with specified resolution (typically 160x120 VGA resolution scaled 4x to 640x480 for visibility); event polling for keyboard presses/releases, mouse clicks, and window close events; scancode translation from SDL keycodes to PS/2 Set 2 scancodes with proper make/break sequences; simulation clock management running thousands of cycles per rendered frame to maintain real-time VGA timing at 50MHz simulation clock; pixel capture accumulating RGB values emitted by the Verilog VGA controller over the course of each frame; texture streaming uploading the captured framebuffer to GPU memory and blitting to the window at display refresh rate; and active board indication rendering visual overlays showing which virtual FPGA board is currently receiving keyboard input.

The main idea enabling this architecture is the separation of concerns: Verilog code remains pure synthesizable RTL with no awareness of the simulation environment; the testbench layer provides a stable interface contract between hardware and software domains; and C++ visualization code operates at the system level, orchestrating clock generation, stimulus injection, and output collection without polluting the hardware design with non-synthesizable constructs. This clean separation means the same Verilog modules can be simulated, synthesized to FPGA bitstreams, or even fabricated as ASICs without modification.

PS/2 Keyboard Interface Simulation

SDL Keycode to PS/2 Scancode Translation

The simulation layer must translate SDL keyboard events into authentic PS/2 scan code sequences. SDL

provides abstract keycodes (SDLK_a, SDLK_RETURN, etc.) that represent logical keys

independent of keyboard layout. I implemented a detailed mapping table from SDL keycodes to PS/2 Set 2 scan

codes, which is the most commonly used PS/2 scan code set. The mapping for alphabetic keys is

non-sequential, as PS/2 scan codes were designed to match the physical keyboard matrix rather than ASCII

order. For example, 'Q' is 0x15, 'W' is 0x1D, 'E' is 0x24, forming a pattern that reflects QWERTY key

positions.

Numeric keys present a particularly interesting case, as their scan codes do not follow the intuitive 0x00-0x09 sequence. Instead, '1' maps to 0x16, '2' to 0x1E, continuing up to '0' which maps to 0x45. This seemingly arbitrary arrangement reflects the historical development of keyboard scan matrices and remains standardized for backwards compatibility. Special keys require careful handling: the space bar is 0x29, Enter is 0x5A, Backspace is 0x66, and Tab is 0x0D. Modifier keys like Shift have distinct scan codes (left shift is 0x12, right shift is 0x59), and their state must be tracked independently to generate proper make/break sequences.

uint8_t sdlKeyToScancode(SDL_Keycode key) {

// Alphabetic keys (a-z) - non-sequential mapping

if (key >= SDLK_a && key <= SDLK_z) {

uint8_t base[] = {

0x1C, 0x32, 0x21, 0x23, 0x24, 0x2B, 0x34, 0x33, // a-h

0x43, 0x3B, 0x42, 0x4B, 0x3A, 0x31, 0x44, 0x4D, // i-p

0x15, 0x2D, 0x1B, 0x2C, 0x3C, 0x2A, 0x1D, 0x22, // q-x

0x35, 0x1A // y-z

};

return base[key - SDLK_a];

}

// Numeric keys (0-9) - irregular mapping

if (key == SDLK_0) return 0x45;

if (key == SDLK_1) return 0x16;

if (key == SDLK_2) return 0x1E;

// ... additional mappings ...

// Special keys

if (key == SDLK_SPACE) return 0x29;

if (key == SDLK_RETURN) return 0x5A;

if (key == SDLK_BACKSPACE) return 0x66;

return 0; // Unknown key

}Make and Break Code Sequencing

Proper keyboard simulation requires generating authentic make/break sequences with correct timing. When a

user presses a key, the simulator immediately sends the corresponding scan code to the Verilog PS/2 keyboard

module by setting scan_code_A = scancode and pulsing key_action_A = 1 for exactly

one simulation clock cycle. This single-cycle pulse triggers the PS/2 serializer module to begin

transmitting the 11-bit frame. When a user releases a key, the simulator must send a two-byte sequence:

first the break code prefix 0xF0, then after a brief delay (typically 100-200 simulation clock cycles to

allow the PS/2 module to process the first byte), the original scan code byte.

I implemented this using a finite state machine with pending release queues to handle this asynchronous

sequencing. Each virtual board maintains a PendingRelease structure with three fields:

state (0 = idle, 1 = need to send F0, 2 = waiting before sending scancode),

scancode (the original scan code to resend after F0), and waitCounter (simulation

cycles elapsed since F0 was sent). When a key release event occurs, state is set to 1 and

scancode is recorded. On the next available simulation cycle where key_action is

not already asserted, the system sends 0xF0 and transitions to state = 2. After waiting for

waitCounter > 100 cycles to ensure the PS/2 module has processed the prefix, the system sends

the original scancode and resets state to 0. This state machine ensures that break

sequences never overlap with make codes or other break sequences, maintaining protocol correctness.

struct PendingRelease {

int state; // 0=idle, 1=send F0, 2=wait then send scancode

uint8_t scancode;

int waitCounter;

};

PendingRelease releaseQueue_A = {0, 0, 0};

// In simulation loop (called each cycle)

if (releaseQueue_A.state == 1 && !key_action_A_pending) {

sendScancodeToBoard(true, 0xF0); // Send break prefix

// State machine advances to 2 after key_action pulse clears

}

else if (releaseQueue_A.state == 2) {

releaseQueue_A.waitCounter++;

if (releaseQueue_A.waitCounter > 100) { // Wait for F0 to process

sendScancodeToBoard(true, releaseQueue_A.scancode);

releaseQueue_A.state = 0; // Reset state machine

}

}PS/2 Clock and Data Generation

The ps2KeyboardVerilator Verilog module as a cycle-accurate PS/2 transmitter that

converts byte-level scan codes into properly timed serial waveforms. The module operates as a finite state

machine with three primary states: KB_0_IDLE waits for key_action assertion and

maintains the PS/2 clock high; KB_1_LOAD_DATA loads the scan code into an internal shift

register and prepares for transmission; and KB_2_DATA_OUT shifts out bits serially, toggling

the PS/2 clock and data lines according to protocol timing. The module includes an internal FIFO queue (16

bytes deep) to buffer multiple scan codes if they arrive faster than they can be transmitted, preventing

keys from being lost in situations such as multiple keypresses or a very high-rate of keypresses.

Clock generation uses a 3-bit shift register (clk_div) that divides the 50MHz simulation clock

down to approximately 8.33MHz PS/2 clock frequency, achieved through the pattern

111 → 110 → 100 → 000 → 001 → 011 → 111. This produces a clock cycle every 6 simulation clocks,

corresponding to $50 \text{ MHz} / 6 \approx 8.33 \text{ MHz}$. The data output sequencer uses a 4-bit

counter to track frame bit position: counter value 0 outputs the start bit (0), values 1-8 output data bits

D0-D7 with LSB first, value 9 outputs the computed parity bit using XOR reduction

parity = ^data inverted for odd parity, and value 10 outputs the stop bit (1). After value 11,

the module deasserts data_ready and returns to idle state, ready for the next scan code.

// PS/2 clock generation via shift register pattern

reg [2:0] clk_div;

always @(posedge Clock) begin

clk_div[2:1] <= clk_div[1:0];

if (data_ready)

clk_div[0] <= ~clk_div[2]; // Shift pattern 111→110→100→000→001→011

else

clk_div[0] <= 1'b1; // Idle high

end

// Data bit sequencing with proper start/data/parity/stop

always @(posedge Clock) begin

if (data_ready & ~clk_div[2] & clk_div[1]) begin // On falling edge of ps2_clk

if (counter == 0) begin

ps2_buf <= 1'b0; // START bit

counter <= counter + 1;

end

else if (counter < 9) begin

ps2_buf <= data[0]; // Data bits D0-D7

data <= {data[0], data[7:1]}; // Rotate shift register

counter <= counter + 1;

end

else if (counter == 9) begin

ps2_buf <= (^data) ^ 1'b1; // PARITY (odd)

counter <= counter + 1;

end

else if (counter == 10) begin

ps2_buf <= 1'b1; // STOP bit

counter <= counter + 1;

end

else if (counter == 11) begin

counter <= 0;

data_ready <= 0; // Frame complete

end

end

end

assign ps2_clk = (clk_ready) ? clk_div[2] : 1'b1;

assign ps2_dat = (ps2_buf | (~data_ready)) ? 1'b1 : 1'b0;VGA Display Simulation and Pixel Capture

VGA Timing and Resolution

I configured the simulated VGA controller to operate at a resolution of 160x120 pixels with 4-bit color depth (16 colors), a deliberately low resolution chosen to minimize simulation overhead while remaining sufficient for text display and simple graphics. Standard VGA timing requires precise horizontal and vertical synchronization pulses that coordinate the electron beam's raster scan pattern (or modern LCD pixel refresh). The simulator generates these signals at the same timing as would be required for real VGA hardware, ensuring that the synthesized FPGA bitstream will produce identical visual output.

For the 160x120 @ 60Hz video mode, the timing parameters are significantly relaxed compared to standard VGA modes (640x480 @ 60Hz requires 25.175 MHz pixel clock), allowing the simulation to run at a lower effective pixel clock derived from the 50MHz system clock. The horizontal timing typically includes a visible region of 160 pixels, a front porch of 8-16 pixels, a sync pulse of 16-32 pixels, and a back porch of 8-16 pixels, totaling approximately 200-224 pixel periods per horizontal line. The vertical timing includes 120 visible lines, a front porch of 2-4 lines, a sync pulse of 2-4 lines, and a back porch of 6-10 lines, totaling approximately 134-138 lines per frame. At 60Hz frame rate, this yields $60 \text{ frames/sec} \times 138 \text{ lines/frame} \times 224 \text{ pixels/line} \approx 1.86 \text{ MHz}$ pixel clock, well within the capabilities of a 50MHz Verilog simulation.

Real-Time Pixel Capture

The C++ visualization layer captures VGA output on a pixel-by-pixel basis during simulation execution. On

each simulation clock cycle (after calling top->eval()), the testbench reads the exposed VGA

port signals from the Verilator model: visible_A indicates whether the current pixel is in the

active display region (not in blanking intervals), xOrd_A and yOrd_A provide the

current pixel coordinates as 10-bit values (supporting up to 1024x1024 resolution), and red_A,

green_A, blue_A provide 4-bit color components (values 0-15). When

visible_A is asserted and coordinates are within the valid 160x120 range, the pixel is

immediately stored in a framebuffer array.

I structured the framebuffer as a three-dimensional array

uint8_t pixelsA[VGA_HEIGHT][VGA_WIDTH][3], where the dimensions represent row index (Y

coordinate), column index (X coordinate), and color channel (R, G, B) respectively. The 4-bit hardware color

values are scaled to 8-bit RGB components using multiplication by 17 (i.e.,

red_8bit = red_4bit * 17), which maps 0→0, 15→255, and provides approximately linear

intermediate values. This scaling is necessary because SDL2 textures expect 24-bit RGB888 format (8 bits per

channel), and simply bit-shifting (e.g., red_4bit << 4) would produce only dark colors in the

upper half of the dynamic range.

// Pixel capture during simulation loop (called every cycle)

for (int i = 0; i < CYCLES_PER_CHUNK; i++) {

top->clock50MHz = 0;

main_time += 10; // 20ns period = 10ns half-period

top->eval();

top->clock50MHz = 1;

main_time += 10;

top->eval();

// Capture VGA pixels when visible

if (top->visible_A && top->xOrd_A < VGA_WIDTH && top->yOrd_A < VGA_HEIGHT) {

pixelsA[top->yOrd_A][top->xOrd_A][0] = top->red_A * 17; // 4-bit to 8-bit

pixelsA[top->yOrd_A][top->xOrd_A][1] = top->green_A * 17;

pixelsA[top->yOrd_A][top->xOrd_A][2] = top->blue_A * 17;

}

}SDL2 Texture Streaming and Rendering

After accumulating a complete frame's worth of pixels (or more realistically, after simulating a sufficient

number of cycles to refresh most of the display), the framebuffer is uploaded to GPU memory via SDL2's

streaming texture API. The process begins with SDL_LockTexture(), which provides a writable

pointer to the texture's pixel data. The framebuffer is then copied row-by-row into the texture's memory

region. Each pixel's RGB components are

written sequentially as three bytes (R, G, B) in the texture's format.

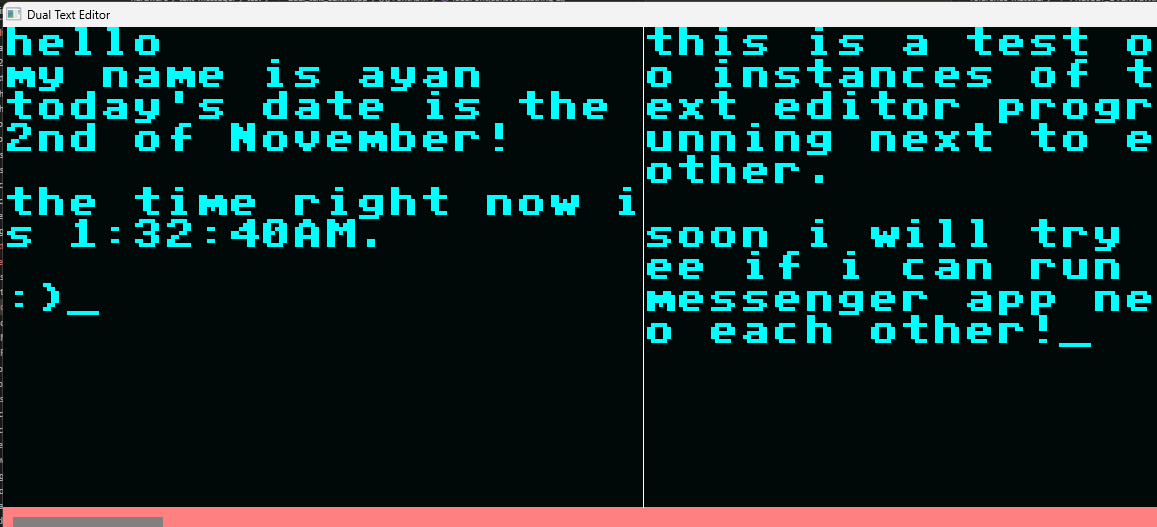

For dual-board simulations, I doubled the texture dimensions horizontally (320x120 logical pixels), and the

left half receives board A's framebuffer while the right half receives board B's framebuffer. After

unlocking the texture with SDL_UnlockTexture(), the texture is rendered to the window using

SDL_RenderCopy() with a destination rectangle scaled by the SCALE factor

(typically 4x), transforming the 320x120 texture into a 1280x480 window for comfortable viewing. A vertical

separator line is drawn between the two board views, and a colored indicator rectangle (green for board A,

blue for board B) shows which board currently receives keyboard input.

// Render frame (called after chunk simulation completes)

void* pixels;

int pitch;

SDL_LockTexture(texture, NULL, &pixels, &pitch);

// Copy board A (left half)

for (int y = 0; y < VGA_HEIGHT; y++) {

for (int x = 0; x < VGA_WIDTH; x++) {

uint8_t* dst = (uint8_t*)pixels + y * pitch + x * 3;

dst[0] = pixelsA[y][x][0]; // Red

dst[1] = pixelsA[y][x][1]; // Green

dst[2] = pixelsA[y][x][2]; // Blue

}

}

// Copy board B (right half)

for (int y = 0; y < VGA_HEIGHT; y++) {

for (int x = 0; x < VGA_WIDTH; x++) {

uint8_t* dst = (uint8_t*)pixels + y * pitch + (x + VGA_WIDTH) * 3;

dst[0] = pixelsB[y][x][0];

dst[1] = pixelsB[y][x][1];

dst[2] = pixelsB[y][x][2];

}

}

SDL_UnlockTexture(texture);

// Render to screen with scaling

SDL_RenderClear(renderer);

SDL_Rect dst = {0, 0, VGA_WIDTH * 2 * SCALE, VGA_HEIGHT * SCALE};

SDL_RenderCopy(renderer, texture, NULL, &dst);

SDL_RenderPresent(renderer);Inter-FPGA Communication Simulation

Dual-Board Text Messenger Architecture

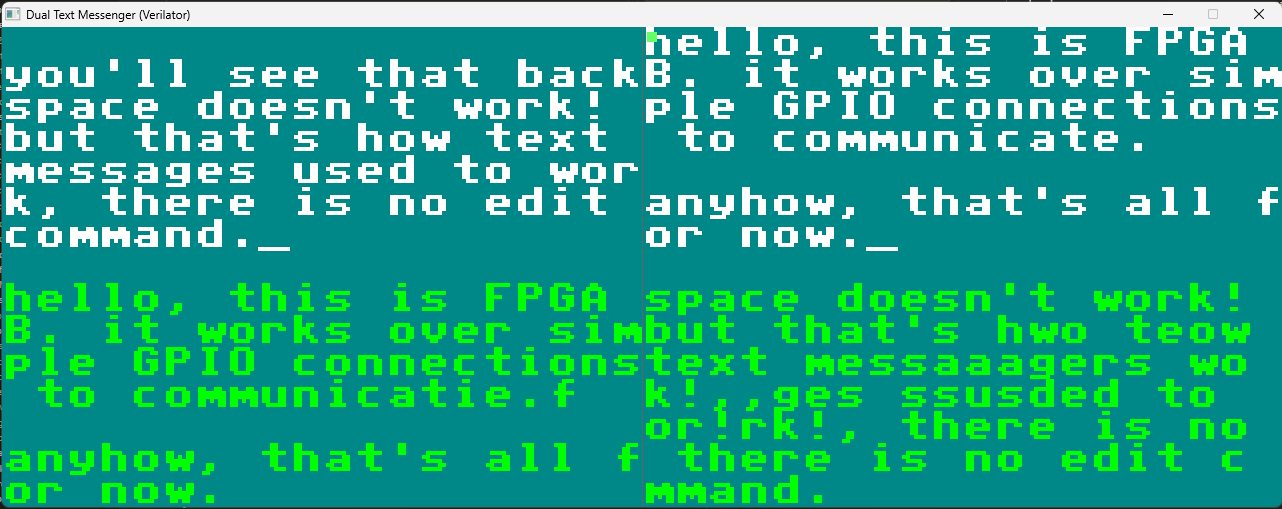

The messenger simulation images above showcase the exact example I built in the ref-verilator

codebase, giving us real-time bidirectional communication between two simulated FPGA boards. Each board

runs an independent instance of the textMessenger module, complete with its own PS/2 keyboard

input, VGA display output, text buffer memory, and communication state machine. The system simulates a

realistic scenario where two physical FPGA development boards would be connected via GPIO pins, with each

board capable of sending 8-bit ASCII characters to its peer. What makes this architecture particularly

powerful for development is the ability to test multi-board communication protocols without requiring

physical hardware, expensive multi-channel logic analyzers, or complex board-to-board debug setups.

I kept the communication protocol deliberately simple to showcase the simulation tool rather than

implement complex networking stacks. Each board exposes four communication ports: commOut[7:0]

carries the 8-bit ASCII character being transmitted, commValid is a single-cycle strobe signal

indicating that commOut contains valid data, commIn[7:0] receives ASCII characters

from the peer board, and commValidIn indicates when incoming data is valid. The testbench

implements the physical wire connections by cross-coupling the ports: commOut_A → commIn_B,

commValid_A → commValidIn_B, commOut_B → commIn_A, and

commValid_B → commValidIn_A. This creates a zero-latency bidirectional link, emulating

perfectly reliable GPIO connections.

// Testbench wire cross-connection (in tbDualMessengerVerilator.v)

wire [7:0] commOut_A, commOut_B;

wire commValid_A, commValid_B;

// Cross-connect: A sends to B, B sends to A

wire [7:0] commIn_A = commOut_B;

wire commValidIn_A = commValid_B;

wire [7:0] commIn_B = commOut_A;

wire commValidIn_B = commValid_A;

textMessenger boardA (

.clock50MHz(clock50MHz),

.resetn(resetn),

.commOut(commOut_A),

.commValid(commValid_A),

.commIn(commIn_A),

.commValidIn(commValidIn_A),

/* ... other ports ... */

);

textMessenger boardB (

/* ... similar connection pattern ... */

);Protocol Timing and Handshaking

The textMessenger module uses a simple valid-strobe (basically bit-blasting) protocol: the

sender places the ASCII

character on commOut and asserts commValid for one clock cycle. The receiver

samples on each rising edge and captures the data when commValidIn is asserted, writing it to

the receive buffer. This unidirectional protocol is lossy if the receiver isn't ready, but its simplicity

makes it very easy for us to implement and test quickly.

I am sure that there are more advanced protocols out there, but this is a good starting point for t least getting this to work nicely. The plan here was to allow for two boards to communicate with each other in the raycasting setup below giving us multiplayer players moving on the same map together. I am told however trying to synchronize the clocks between the two FPGAs will require clock domain crossing.

The messenger simulation speeds up inter-FPGA communication development by skipping the synthesis-program-test cycle. On real hardware, each iteration takes 30-60 minutes where you have to modify Verilog, synthesize and program both FPGAs, wire them up, run tests, analyze with oscilloscope, repeat. This is way better.

Build System and Compilation Process

Makefile Architecture

The build system runs through a very structured Makefile that manages Verilator compilation,

C++ compilation, and executable linking in a reproducible manner. The Makefile defines several key

variables: VERILATOR_FLAGS specifies compilation options including --cc (generate

C++ code), --exe (create executable), --Mdir obj_dir (output directory), and

warning suppressions like -Wno-WIDTHTRUNC (ignore width truncation warnings common in

real-world Verilog); VERILOG_SOURCES_MESSENGER lists all Verilog files including RTL modules

(vgaDriver.v, ps2Driver.v, textMessenger.v) and testbench wrappers

(tbDualMessengerVerilator.v, ps2KeyboardVerilator.v); and LIBS and

LDFLAGS configure SDL2 linking with MinGW-specific static/dynamic library flags.

The compilation process proceeds in multiple stages:

- The

copy_mem_filestarget searches multiple possible locations forfont8x8.memandscancode.mem(font bitmap data and PS/2 scancode lookup tables) and copies them to the current directory, as Verilator's$readmemh()function expects memory initialization files in the working directory. - The

dualMessengerVerilatortarget invokes Verilator with all Verilog sources and the C++ testbench file (dualMessengerVerilator.cpp), specifying--top-module tbDualMessengerVerilatorto designate the testbench as the root of the module hierarchy. - Verilator generates C++ code in

obj_dir/and creates a makefile (VtbDualMessengerVerilator.mk). - The Makefile then appends SDL2 linking flags to the generated makefile by echoing

LIBS += $(LIBS)into the generated file, working around Verilator's lack of native SDL2 support. - Finally,

make -C obj_dir -f VtbDualMessengerVerilator.mkinvokes the generated makefile to compile the Verilator runtime library, generated C++ sources, and testbench C++ into a final executable.

# Verilator flags

VERILATOR_FLAGS = --cc --exe \

-Wall -Wno-fatal \

-Wno-WIDTHEXPAND -Wno-WIDTHTRUNC -Wno-UNUSEDSIGNAL \

--Mdir obj_dir \

-CFLAGS "$(CXXFLAGS)"

# Verilog source files for messenger

VERILOG_SOURCES_MESSENGER = \

../vgaDriver.v \

../ps2Driver.v \

../textMessenger.v \

tb/ps2ClkDatVerilator.v \

tb/ps2KeyboardVerilator.v \

tb/tbDualMessengerVerilator.v

# Build messenger executable

dualMessengerVerilator: copy_mem_files $(VERILOG_SOURCES_MESSENGER) $(CPP_SOURCE_MESSENGER)

$(VERILATOR) $(VERILATOR_FLAGS) \

$(VERILOG_SOURCES_MESSENGER) \

$(CPP_SOURCE_MESSENGER) \

--top-module tbDualMessengerVerilator \

-o dualMessengerVerilator

@echo 'LIBS += $(LIBS)' >> obj_dir/VtbDualMessengerVerilator.mk

@echo 'LDFLAGS += $(LDFLAGS)' >> obj_dir/VtbDualMessengerVerilator.mk

$(MAKE) -C obj_dir -f VtbDualMessengerVerilator.mk

cp obj_dir/dualMessengerVerilator.exe .Optimization and Performance Considerations

The simulation for the messenger runs at roughly 2-5 MHz effective clock speed, meaning 50MHz hardware clock simulation executes in $50 / 2.5 \approx 20\times$ real-time. This slowdown factor is acceptable because human interaction (keyboard input, visual observation) operates at much slower timescales. I deliberately chunk cycle execution (simulating 8,333 cycles between frame renders) to maintain responsive 60fps display updates while maximizing throughput. This is similar to how FPS is mantained in the BareMetal Logic game when we take as much time to calculate TPS and then spend the rest of the cycle rendering to screen to mantain 60 FPS.

// Chunked simulation for responsiveness

const int CYCLES_PER_CHUNK = 8333; // ~1/100th of a 60Hz frame

while (running) {

SDL_PollEvent(&event); // Handle user input

for (int i = 0; i < CYCLES_PER_CHUNK; i++) {

// Simulate one clock cycle

top->clock50MHz = 0;

top->eval();

top->clock50MHz = 1;

top->eval();

// Capture VGA pixels inline

if (top->visible_A && top->xOrd_A < VGA_WIDTH && top->yOrd_A < VGA_HEIGHT) {

pixelsA[top->yOrd_A][top->xOrd_A][0] = top->red_A * 17;

pixelsA[top->yOrd_A][top->xOrd_A][1] = top->green_A * 17;

pixelsA[top->yOrd_A][top->xOrd_A][2] = top->blue_A * 17;

}

}

// Render accumulated frame

SDL_LockTexture(texture, NULL, &pixels, &pitch);

/* ... copy framebuffer to texture ... */

SDL_UnlockTexture(texture);

SDL_RenderPresent(renderer);

}(Ongoing) Raycasting Engine Development

Rapid Prototyping of Complex Graphics Algorithms

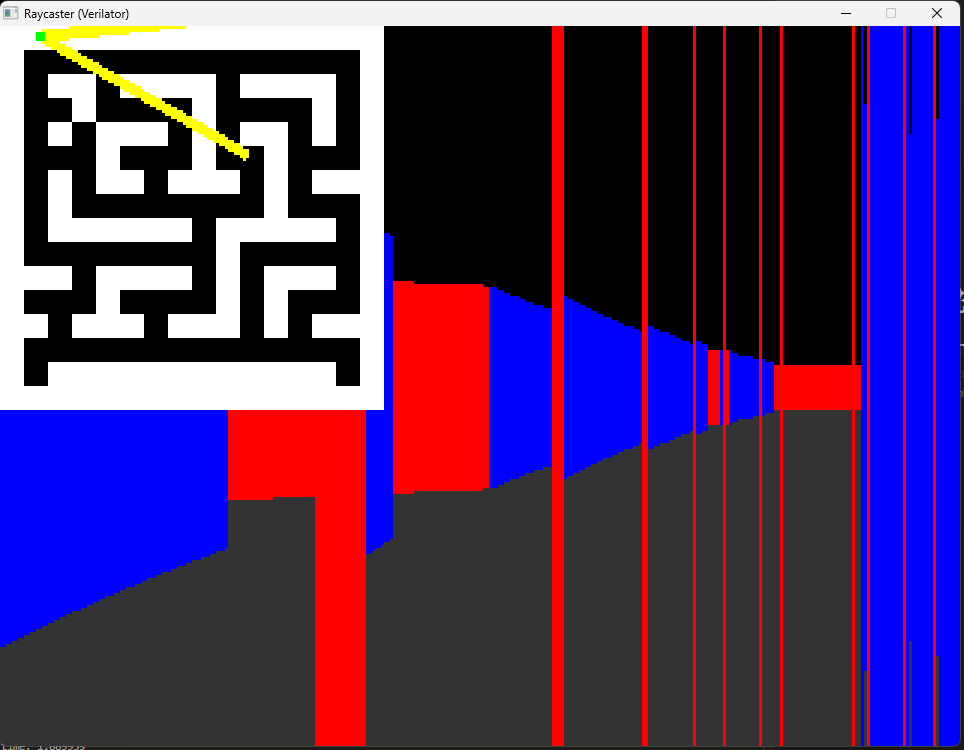

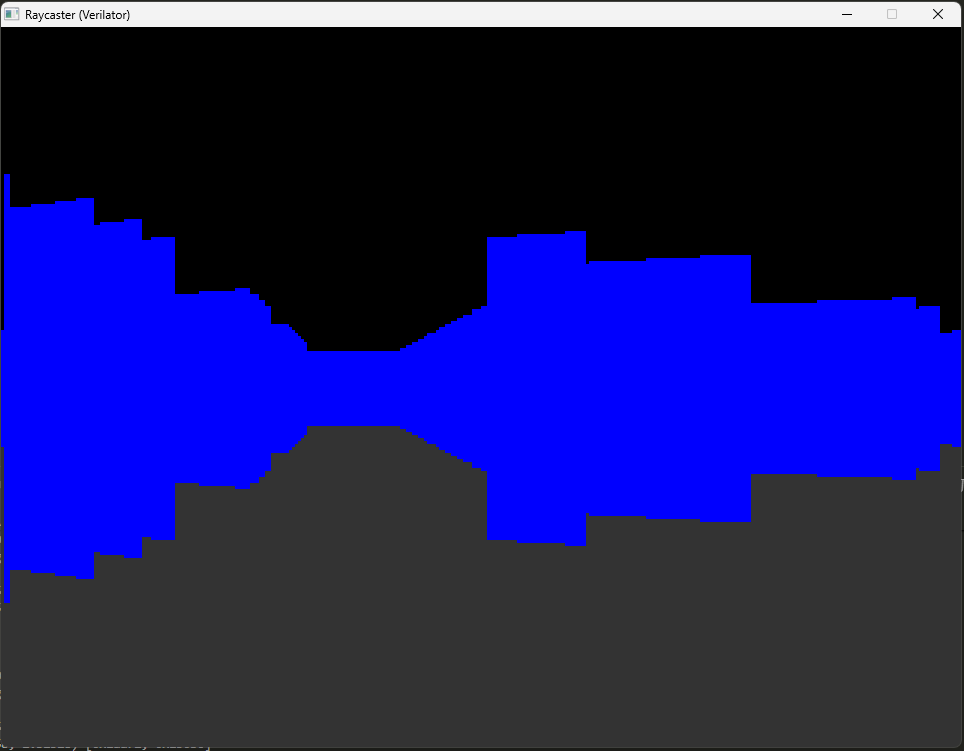

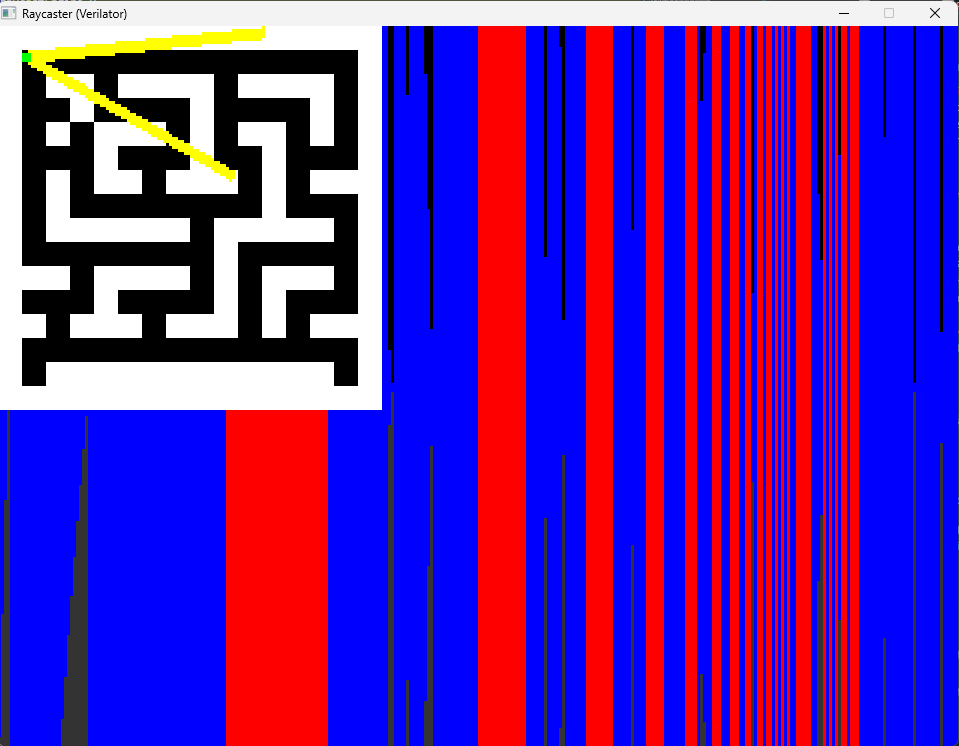

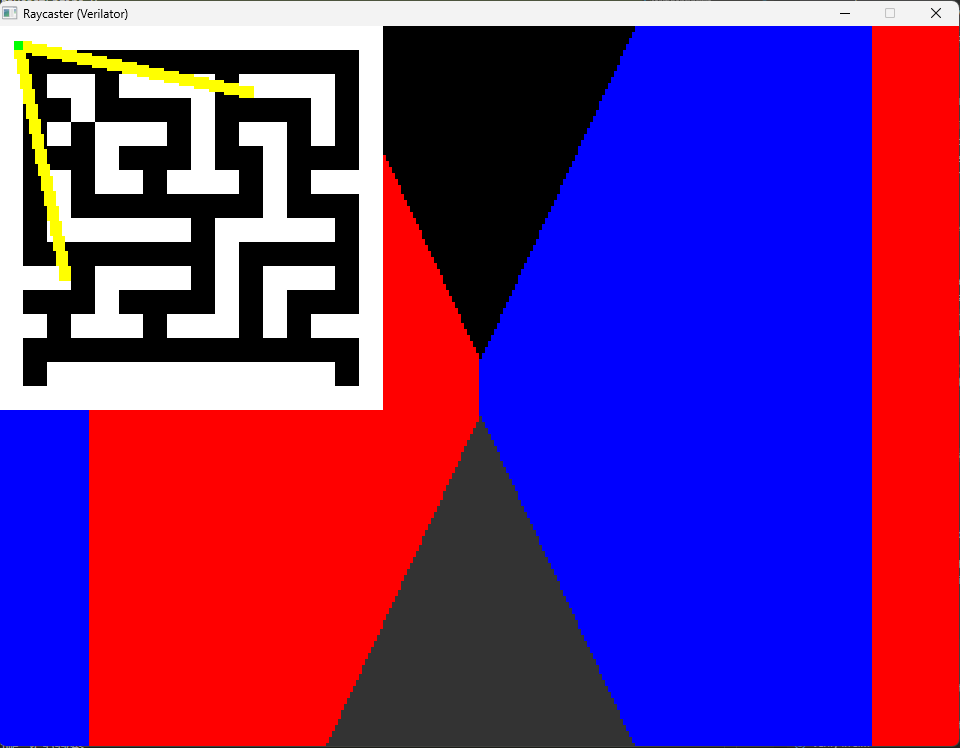

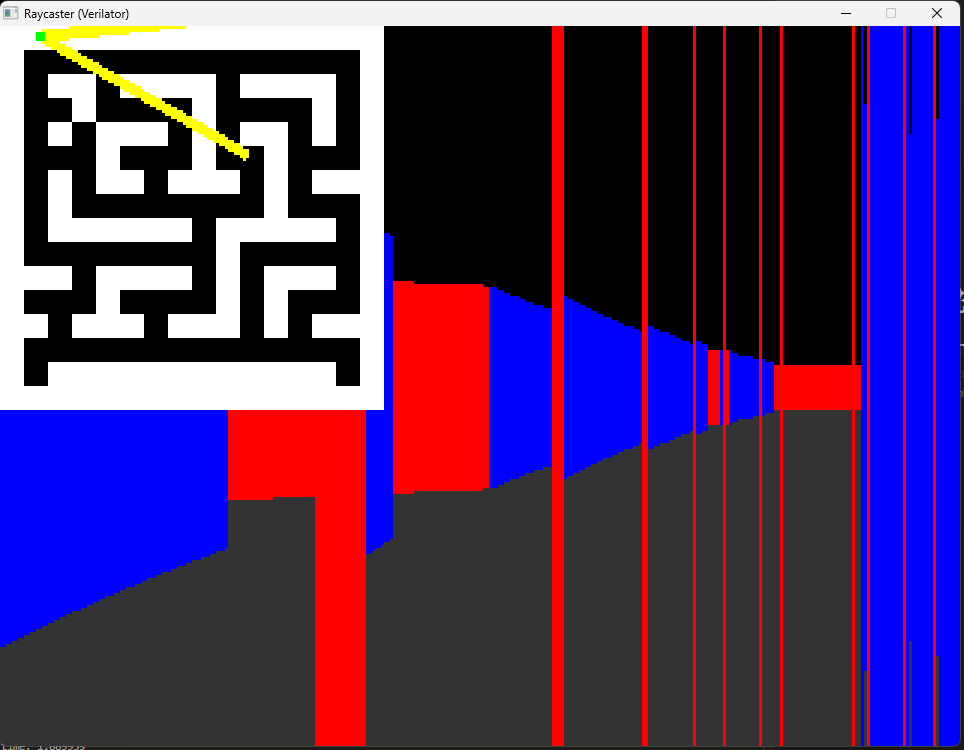

The above images shows the iterative development of a raycasting engine implemented in Verilog and simulated using this tool. Raycasting is a 2.5D rendering technique used in games like Wolfenstein 3D, where a 2D grid-based map is rendered with perspective projection by casting rays from the player's viewpoint to detect wall intersections. Implementing raycasting in hardware is non-trivial (at least for me!), requiring fixed-point arithmetic for fractional coordinates, trigonometric lookup tables for angle computations, and pipelining of the ray-marching algorithm (given that raycasting is a sequential ray-marching algorithm) to meet timing constraints. The images show off the development process, where initial attempts produce scrambled or empty output, suggesting fundamental issues with coordinate transformations or memory addressing; subsequent iterations show partial rendering with visible artifacts like incorrect wall heights, missing textures, or coordinate system inversions; and near-final versions exhibit recognizable 3D corridor perspectives with minor remaining glitches.

Fixed-Point Arithmetic Debugging

Raycasting algorithms heavily rely on fixed-point arithmetic because floating-point units are expensive in FPGA resource utilization. A typical fixed-point representation uses $Q_{m.n}$ format, where $m$ integer bits and $n$ fractional bits combine to represent values in the range $[-2^{m-1}, 2^{m-1})$ with precision $2^{-n}$. For example, $Q_{8.8}$ format uses 8 integer bits and 8 fractional bits, representing values from -128 to +127.99609375 with precision 0.00390625. Fixed-point multiplication requires some care in handling as when we are multiplying two $Q_{8.8}$ values we may produce a $Q_{16.16}$ result that must be right-shifted by 8 to restore $Q_{8.8}$ format, as $(a \times 2^{-8}) \cdot (b \times 2^{-8}) = (a \cdot b) \times 2^{-16}$.

Here I encountred issues three major issues with my verilog: one was overflow in intermediate calculations

causing

wraparound artifacts (walls appearing at impossible angles); the next was incorrect shift amounts leading to

scale errors

(walls appearing 2x or 4x too tall/short); and lastly sign-extension bugs in signed fixed-point subtraction

(negative coordinates wrapping to large positive values). The simulation tool's debug capabilities

allowed me to add $display() statements in the Verilog ray-marching loop to print

intermediate fixed-point values into the console, inspect coordinate transformations step-by-step, and

validate that ray

intersection calculations match expected results just like one would do using a software debugger.

Final Working Implementation

The image above shows the end result of the development process, it has't yet been exactly working as expected but it gets quite close.

The raycasting engine uses a pipelined architecture where each clock cycle processes one pixel column.

- Computes the ray direction based on player angle and current column index using precomputed sine/cosine lookup tables.

- Performs DDA ray marching through the 2D map grid using fixed-point increments.

- Detects wall intersections by checking map cells until a non-zero value is found.

- Calculates wall height using the formula $h = \frac{k \cdot f}{d}$ where $k$ is a scaling constant, $f$ is the focal length, and $d$ is the perpendicular distance to the wall.

- Outputs RGB color values with distance-based shading applied.

At 160 pixels horizontal resolution, the engine can achieve $\frac{50 \text{ MHz}}{160 \text{ pixels}} \approx 312 \text{ kHz}$ frame rate theoretically, though practical implementations are limited by VGA timing to 60Hz.

Memory Initialization and Resource Files

Font ROM and Character Rendering

The text display functionality relies on a font ROM containing bitmap representations of ASCII characters. I

created the font8x8.mem file to store a classic 8x8 pixel font where each character occupies 8

bytes (one byte per row), with each bit representing a pixel (1 = foreground, 0 = background). The font data

is loaded into Verilog block RAM using the $readmemh() system task during module

initialization, creating a synchronous ROM that can be indexed by character code to retrieve pixel patterns.

Character rendering is performed by the VGA controller's pixel generation logic. For each visible pixel at

coordinate $(x, y)$, the system computes the character grid position $(\text{charX}, \text{charY}) =

(\lfloor x / 8 \rfloor, \lfloor y / 8 \rfloor)$, reads the character code from the textBuffer

at that grid position, computes the pixel offset within the character $(\text{pixelX}, \text{pixelY}) = (x

\bmod 8, y \bmod 8)$, looks up the font bitmap row using fontROM[charCode * 8 + pixelY], and

extracts the pixel bit using fontRow[7 - pixelX]. If the bit is 1,

foreground color is output; if 0, background color is output. This simple pipeline operates entirely in

combinational logic between the pixel clock and the VGA output registers, adding zero cycles of latency.

// Font ROM initialization

reg [7:0] fontROM [0:2047]; // 256 characters * 8 rows

initial begin

$readmemh("font8x8.mem", fontROM);

end

// Character rendering pipeline (combinational)

wire [4:0] charX = xOrd[9:3]; // x / 8

wire [3:0] charY = yOrd[9:3]; // y / 8

wire [7:0] charCode = textBuffer[charY * 20 + charX]; // 20 chars wide

wire [2:0] pixelX = xOrd[2:0]; // x % 8

wire [2:0] pixelY = yOrd[2:0]; // y % 8

wire [7:0] fontRow = fontROM[charCode * 8 + pixelY];

wire pixelBit = fontRow[7 - pixelX];

assign red = pixelBit ? 4'hF : 4'h0; // White or black

assign green = pixelBit ? 4'hF : 4'h0;

assign blue = pixelBit ? 4'hF : 4'h0;Scancode ROM and PS/2 Decoding

I created the scancode.mem file as a lookup table mapping PS/2 Set 2 scan codes to ASCII

character values, handling both unshifted and shifted variants. The ROM is organized as a 256-entry table

where the scan code is used as an index to retrieve the corresponding ASCII value. For example, scan code

0x1C (A key) maps to ASCII 0x61 ('a') when unshifted and 0x41 ('A') when shifted. The PS/2 driver module

maintains a shift state flag that is set on receiving scan codes 0x12 or 0x59 (left/right shift make codes)

and cleared on receiving 0xF0 0x12 or 0xF0 0x59 (shift break sequences).

The ASCII conversion process operates as follows: when a scan code is received (excluding 0xF0 prefix and

shift keys), the module reads asciiTable[scanCode] to get the unshifted ASCII value, reads

asciiTable[scanCode + 128] to get the shifted ASCII value (stored in the upper half of the

table), and selects between them using the current shift state flag. The resulting ASCII character is then

written into the text editor's buffer and displayed on the VGA output.

Future Developments

I would like to develop a tool that enables quick development of programs using high-level HDL languages like Silice while also writing C programs. This would allow developers to very quickly write highly performant programs for MCU-FPGA systems such as pairings like ATMegaX-IC40X, enabling highly performant, low power consumption systems where we can perfectly optimize for both performance and power efficiency. The platform would expose a unified toolchain for cross-compilation, cycle-accurate co-simulation, and easy packaging so prototypes can be verified and iterated quickly just like FPGAScope or the raycaster was.

A cool idea would be to have a very limited piece of hardware like that run a full game like Comanche: Maximum Overkill from 1992 on a power consumption of less than 1W (or that order of magnitude when comparing how much energy it took to run back in 1992).

The tool would allow someone to very quickly write in C (or C++), find the functions or algorithms that take the longest by some nice development environment that automatically places timers and then allows the user to implement the slow (or costly functions) in some high-level HDL like Silice (as we can get the biggest performance gain as it is the highest cost) and compile all in one integrated test environment just like I've done above.

Image source: Rock Paper Shotgun - Voxel Pop's New Comanche Campaigns